INTERVIEW by DENNIS MARTIN

INTERVIEW by DENNIS MARTIN We continue our interview with Marcus Wynne, a former US Federal Counter-terrorist operative, who is now involved in VIP & Corporate Security, and defensive training.

In part one we discussed the breakthroughs with Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP) applied to close-quarter combat, we presented the first British discussion of the US Army's Jedi Project. We then covered your current work in training women through the innovative Nikita Project. I would like to emphasise that this type of training, despite having a strong theoretical base, is in fact very much "hands on" and practically orientated. Indeed, a major feature of NLP is the involvement of as many types of sensory input:- visual, auditory, and of course kinaesthetic, or "doing it/feeling it".

DEN: Marcus your training programs based on advanced human learning technologies have very clearly defined outcomes. Obviously, the final validation is the ability to perform... as long as the test is realistic. I think some of the problems you are encountering with the inertia of some current organisations, is the fact that the test medium they use is not valid and does not correlate to the real worldMARCUS: That's exactly what we're seeing. A friend of mine who works in the intelligence community as a paramilitary/firearms instructor made reference to an historical project that he's working on. One of the things that he's analysing is that many of the survivors of World War Two Special Ops, the American OSS and the British SOE, whose close-quarter-battle training was very short, very rudimentary, but very intense, and focused on scenario-based training. What is amazing is that these old timers, who are in their seventies and eighties, are still able on demand to re-create and utilise those combative shooting skills that they learned years ago, without ever practising! And they can do that under stress, while we have young 25-30 year old police officers who after 13 weeks of intensive firearms training, and qualifying once per month, are still losing gunfights at under seven yards! What is it that we're doing wrong? Our thesis, our supposition is that we are failing to involve them in a situational environment that as closely as possible approximates the reality in which they will use those skills. And in doing that we're doing ourselves a disservice as instructors, while we're doing a grave injustice to our students.

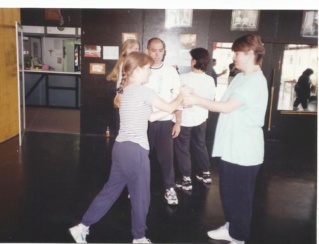

[Mika and Den demonstrate a partner drill, while Marcus explains]DEN: Having worked with you over the past seven or eight years I know you share our opinion that there is no separation between the different aspects of close-quarter battle.... it's all fighting. We don't separate out the unarmed combat from the knife training; and we don't split the hand-to-hand from the tactical pistol work. So do you see the scenario-based training, and the NLP approach as being just as significant to unarmed combat?

[Mika and Den demonstrate a partner drill, while Marcus explains]DEN: Having worked with you over the past seven or eight years I know you share our opinion that there is no separation between the different aspects of close-quarter battle.... it's all fighting. We don't separate out the unarmed combat from the knife training; and we don't split the hand-to-hand from the tactical pistol work. So do you see the scenario-based training, and the NLP approach as being just as significant to unarmed combat?MARCUS: Absolutely, absolutely. That's not only an outgrowth of experience in terms of the operational venue, both in the military and governmental sectors; but it's also an outgrowth of martial arts background. The martial arts I've had the longest acquaintance with are the Filipino martial arts, that make no distinction between knives, stick and in a lot of instances guns in close-quarter battle, along with empty hand techniques. It's all one flow, it's all one technique, and it’s all one mindset. That universality is what we lose so often with that artificial separation of armed and unarmed training. We lose track of the fact that what we are in fact doing is we are fighting, and we are using a tool. We are not doing marksmanship; we are fighting with the gun.

DEN: Let's move on to another interesting concept which you presented on the Ohio BG Course. During your class on the Mental Aspects you introduced a concept called The OODA Loop, which I understand you adapted from the training of fighter pilots. Perhaps you can share that with our readers?MARCUS: Gladly. OODA is an acronym for OBSERVATION-ORIENTATION-DECISION-ACTION. It's a three-dimensional model; it's the Situational Awareness model that was developed first of all in studies of jet fighter pilots, who operate in a three-dimensional environment. Then it's been adopted as the latest strategy for the light infantry units, Special Ops units, and was applied with the most devastating effect by the US military planners during Desert Storm.

[Slacky, who has trained with Marcus in UK and USA, here discusses the OODA Loop]

[Slacky, who has trained with Marcus in UK and USA, here discusses the OODA Loop]Specifically, the theory behind OODA is that it is a continual loop, an information-processing loop, that the human being goes through in terms of an evaluation of the environment. The "O" stands for Observation, that is when the operator is in the situational awareness mode of relaxed alertness, what Jeff Cooper calls “Condition Yellow”, the individual constantly scans the environment and identifies something; then Orients, (the second "O"). That is, they focus their attention on whatever they have observed and make an evaluation based on their experience, their intelligence, and their "feel" of the situation.

They, "orient", they make a determination, is this a threat? Is this something I have to do something about, or not? At that point they go into the "D", which is the Decision cycle...what am I going to do? Am I going to put into effect pre-arranged plans, how am I going to act on this? Which is "A", which is Action. You put into effect what you have decided to do. You act, then you go back into the loop of "O", observing; you observe how the situation has changed as a result of your action. It's an ongoing, circular and three-dimensional process...and what the theory is, whether it's personal combat, or military strategy, is you want to break your opponents OODA Loop.

You win the fight by assessing the situation faster, and therefor getting inside your opponents OODA Loop, where you're turning faster and acting faster. When someone is observing me I want to be past orientation into decision, or even most of the way into action. In other words I've lapped them, if you can imagine a circle within a circle. By the time that opponent has oriented on me it should be all over.

DEN: Can you give readers an example of how they might apply the OODA Concept?MARCUS: Certainly, you can apply that in the martial arts venue constantly, in terms of, for example street awareness. You're walking down a street and you see someone approaching you. You're observing you're in tune with your surroundings. You orient on that person based on your experience and your evaluation of the situation. You determine is that person a threat? Then you decide what am I going to do.... am I going to cross the street, am I going to avoid this, am I going to prepare myself to defend myself, am I going to take my weapon out...what am I going to do? Then at that point you act. You either choose to do something, or choose not to do something. You may cross the street. Then you go back into observation...the situation has now changed. So, is there going to be a new orientation? If you cross the street and that individual crosses it too, that orientation kicks in a different decision/action cycle, which you then go into. That would be just one example.

One way of breaking that would be, if I saw someone coming to me and I was in a bad neighbourhood, if I wanted to break their cycle I might deny them observation, I might step into the shadows, or, turn around and walk the other way. I would deny them the ability to observe and orientate on me. By that I'm inside of their cycle...I may have broken the entire cycle of violence that may be escalating.

It's a real elegant concept that serves very well for VIP close-protection because most often we're in the situation of a small Spec-Ops unit in that there's only those resources we bring with us. We don't have the back-up and we have to out-think the opposition. We have to be smaller, faster, more mobile; that's how we win our fights, because we assess the situation to avoid the trouble. We win because we assess faster and we act faster than our opponent does.

DEN: Great concept, with obvious relevance to the individual martial artist too!

DEN: Great concept, with obvious relevance to the individual martial artist too!

As a final point while working together over the past weeks as a Bodyguard Training Team you, I and Evan Marshall have had many hours of off-duty discussion on the directions that specialised defensive training is taking. All agree that we our still only just scratching the surface, and that over the next few years there will be really significant advances in defensive training. Can you comment?MARCUS: I absolutely agree. I think that where we are at, in terms of combatives, whether it's martial arts, unarmed combatives or, close-quarter-battle. Whether in the private, governmental or, military sphere; whether in the counter-terrorist venue, or in the military spec-ops venue; what we have discovered is that it all comes back to what has been talked about for two thousand years. The weapons are irrelevant...we've got the most advanced handguns and everything else...it really is irrelevant. What's important is the mind. What's important is how effective we make our operators, whether they be an unarmed guy working the door in a bar in Liverpool, or, whether it's an undercover operator working in the middle of Beirut; we still have to instil that the real weapon is the mind.

[Marcus and Den in Minneapolis]

[Marcus and Den in Minneapolis]Where we are really going to stretch training is, we've spent millions of dollars on state-of-the-art shooting facilities, the best guns and the latest ammo; but when we look at the results of the close-range reactive scenarios we are not doing any better. That means there is something fundamentally wrong. What we need to do then, at this point, is to address that variable, that is, what is the mindset, where's the mental orientation? I believe we have an ethical and moral obligation, to give our students the very best mental preparation we can, so they can survive in those kind of circumstances. There's no excuse for us to back away from that.

We've encountered a lot of resistance, as we've already mentioned, from many people who have spent so much time, money and energy committing to these institutional approaches to training, and are very resistant to the idea of taking in new and advanced human learning technologies. The thing is, where the real progress will be made, is going to be made internally, it's going to be made mentally. It's going to be in the mental training and conditioning that we are experimenting with right now. That's where the big leap is going to be made, and that's where I think we'll see the increase in survivability.

DENNIS: Marcus, I know that following the September 11th attack you appeared on numerous TV programs as a tactical expert, especially relating to aviation security. What are your thoughts on the attack, how we can prepare against terrorist violence, and the implications for self-protection training?MARCUS: I guess my biggest response was one of dismay and anger -- as a security professional I and others have been banging the gong about the vulnerabilities in the domestic United States for a long time. Especially those vulnerabilities in the civil aviation security system, which were underscored by the terrorist attacks on 11 September. Those terrorists didn't kick holes in the security fence around aviation, they utilised long standing loopholes and utilised them very well.

[Training for Hostage rescue/bus assault]

[Training for Hostage rescue/bus assault]As for preparing against terrorist violence, the biggest tool we need is our own situational awareness. We need to pay attention to what is going on around us and make sure we notice what is out of place, and if we're not in the security business we need to know how to bring attention of the authorities to what we think is out of place. And we need to be prepared to take matters into our own hands, as did the passengers on the fourth hijacked plane, the one that went down in Pennsylvania.

That leads to the implications of the attack for self protection. There is the matter of situational awareness and being aware and educated as to what to look for. And it's not enough to know what to look for and to recognise it when we see it; we have to be prepared with a plan to deal with it. That plan might mean bringing suspicious activity to the attention of the proper authorities, or it might mean that we will have to stand up in the aisle of a plane being hijacked and become part of the solution. That means you need to be prepared, first mentally, then physically, with all the elements of your training. That then leads to be being responsible for your training, making sure that you are getting the best possible training as well as getting the best possible out of your training, which means you must ensure that you are training the mind appropriately as well as the body, whether with empty hand techniques or with weapons. That requires a serious commitment, and one needs to be sure that they pursue their training with that seriousness.

DENNIS: You mention the importance of "situational awareness" How can the individual train to increase and develop this? MARCUS: Situational awareness in the individual is formed from three things: genetic predisposition to general alertness, which you're born with and can't do anything about. Secondly, your life experiences, which is the sum total of everything that has happened to you since the womb, and thirdly, your training. Some people's life experiences predispose them to greater situational awareness, especially people who have suffered physical abuse at an early age or been exposed to violence like living in a war zone or a blighted neighbourhood. The training is the biggest variable that can increase situational awareness. Training needs to concentrate on creating experiences -- training that adds to the experience leg of the tripod is much more effective than that which is presented in a sterile "classroom" manner. Situational awareness has a physical component directly related to use of the vision; you've done exercises with me and on your own on enhancing the use of peripheral vision and its concomitant effect on general alertness. The other part is learning how to utilise one's own individual OODA loop, which I assume you'll talk about at some point, and understanding how an opponent utilises their OODA loop. Learning how to use one's senses, and increasing one's acuity to behavioural cues, and utilising the OODA loop -- that's how you can increase and develop the basic sense of situational awareness you're born with.

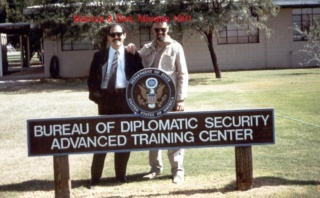

[Den, Lofty and Marcus, during a US Course]DENNIS: You were the first to research the work of Colonel Boyd and introduce it into the Tactical Training Community. Since then, everyone and his dog is teaching the OODA Loop. We covered the concept in an earlier part of this interview, but how do you see training in Situational Awareness, specifically utilising the OODA Loop has developed in the past couple of years?

[Den, Lofty and Marcus, during a US Course]DENNIS: You were the first to research the work of Colonel Boyd and introduce it into the Tactical Training Community. Since then, everyone and his dog is teaching the OODA Loop. We covered the concept in an earlier part of this interview, but how do you see training in Situational Awareness, specifically utilising the OODA Loop has developed in the past couple of years?MARCUS: Situational awareness has made it into the vocabulary of trainers in the course of recent years. There was a lot of talk about general awareness, but the specific language didn't make it in until I and others such as yourself introduced it. There's been a sea change in training in the US in recent years, with a greater emphasis on aspects of mental preparation and mindset. The standard for many years was the Cooper Colour Code and the Principles of Personal Protection; now as an adjunct or supplement (but in my mind equal partners, as they do complement one another) the OODA loop and the concept of situational awareness has come to the forefront. I think the tactical training community, especially in the field of law enforcement and private sector and government, anywhere they don't draw directly from the military, has realised that inculcating the appropriate mental attitude is the essential part of training that has been overlooked. There's been too much emphasis on tactics and gear in the past, and while mindset is mentioned as the third leg of the combat triad, not enough has been done to ensure the appropriate mindset is trained in. That's changing now. I think the difficulty was that mindset was something easy to describe but not so easy to train in. Also, it tends to be hard to evaluate on the same way a tactical scenario can be scored or basic marksmanship can be used to qualify. That's where the paradigm of accelerated learning and compressed curriculum drawing from neural based learning can be of so much use, as you've seen in your own brilliant work on utilising neural based learning for combatives.

DENNIS: You broke new ground in the training of women with the NIKITA PROJECT, which was a big success. How did you differentiate between training women and training the guys? MARCUS: Training women, especially women with a history of violence done to them, is a whole different ball game from teaching men. With any student group, you have to understand the students and have a clear picture of what it is that is motivating them to come to you for training. Then you have to figure out the right language and presentation to communicate that to them. With the NIKITA PROJECT I was working with a large number of women who had survived violence.

[Nikita group in RSA]

[Nikita group in RSA]So I had to find a way to get them to overcome the social inhibitions against women being violent and accessing the state of self defence that everyone carries around with them. I had to find a way of first accessing their anger and then channelling it into appropriate actions. With guys, it's pretty easy to find a way to do that. Women have more societal inhibitions about both dealing with violence, whether receiving it or delivering it. So you have to think through clearly and spend the time up front understanding what it is they want and being sensitive to the special needs of the abused. And you have to be switched on in front of the class and pay attention to what is working and what is not. That's very important. Lots of instructors, they get on a roll from their lesson plan and they're not paying attention to the feedback they get from the students, all the nonverbal and verbal cues that tell you whether they're getting it or not. It's especially important to do that when teaching female abuse survivors, because they can shut down or have a nervous breakdown right in front of you if you're not careful. I found it to be very helpful to have women assistant instructors in he class with men who could be a sympathetic ear to women that were foundering.

DENNIS: On our courses I am frequently approached by guys who are interested in applying NLP to their CQB training, but when they try to find out more, most of the books are concerned with therapy. We both know that right from the earliest days NLP was deeply involved in tactical training. Richard Bandler did work for the US Intelligence Community, the Israeli Commandos, and the US Army weapons training branch. We have already discussed the Jedi Program which Wyatt Woodsmall and Tony Robbins presented. Books like “Turtles all the way down” are very far removed from tactical application! Have you any advice as to how readers can find out more of this aspect?

DENNIS: On our courses I am frequently approached by guys who are interested in applying NLP to their CQB training, but when they try to find out more, most of the books are concerned with therapy. We both know that right from the earliest days NLP was deeply involved in tactical training. Richard Bandler did work for the US Intelligence Community, the Israeli Commandos, and the US Army weapons training branch. We have already discussed the Jedi Program which Wyatt Woodsmall and Tony Robbins presented. Books like “Turtles all the way down” are very far removed from tactical application! Have you any advice as to how readers can find out more of this aspect? MARCUS: The most important NLP aspects to apply to CQB training are behavioural cue acuity and state management, and that is advanced NLP work. The modifications to the therapeutic exercises that I've done and that you've built on and developed aren't really set down anywhere.

[Marcus monitoring trainees in a “kill house”]

[Marcus monitoring trainees in a “kill house”]The CQB student is likely to be swamped with a lot of useless information pertaining to therapy in their search, however, they can find some books on the application of NLP modelling to sports skills which might be a useful start. The intelligence and special ops community has hired consultants to do and develop training for them in NLP, but the state management piece and the specific elements of behavioural cue acuity as applied to CQB were things I developed. NASA, before they hired me as a consultant, spent two years searching for consultants who could do that -- they only found me. When I did a demonstration class for the head of paramilitary training for the CIA (our mutual friend Ed), he told me that the CIA had spent a great deal of money trying to do what I was doing in those classes -- and they'd failed to duplicate the results. So the short answer is that you and I and Rick Faye in Minneapolis and Dave Spaulding in Ohio, are the ones writing that book, and that is where the real advances have been made.

DENNIS: So the concepts outlined in this interview series are a rare written distillation of what is needed to augment CQB with NLP and other neural-based technologies? MARCUS: Absolutely!

DENNIS: You mentioned your work with NASA. It's not widely known that the Space Agency is deeply involved in high-stress operational survival. I attended a presentation on mindset by the FBI and they referred to NASA as the lead agency in the field. Why is that, and what kinds of areas did you cover with them? MARCUS: Well, if you think of the stress an astronaut goes through, when they're on the launch pad on top of the equivalent of a hydrogen bomb in explosive, and they have to ride that bomb into space, a hostile environment to life itself, and a long, long way from any help, it starts to become clear why they're so interested in high stress management. NASA is deeply involved in discovering and developing ways to manage stress in an operational environment, as everything they do is inherently dangerous. The Psychological Services Department in Medical Sciences Branch is where the work is being done, under the guidance of Dr. Al Holland, who I worked for and with on a number of projects. The areas I specifically covered with them included adapting neural based learning and accelerated learning protocols to the entire training flow and to the emergency procedures for the space shuttle and the international space station. I did a study of the training flow and it's strengths and weaknesses, especially in the area of emergency procedures. NASA is also deeply involved in the training and development of situational awareness, and I was able to draw on a lot of their research while I was down there, which helped me develop the situational awareness exercises which we've done together.

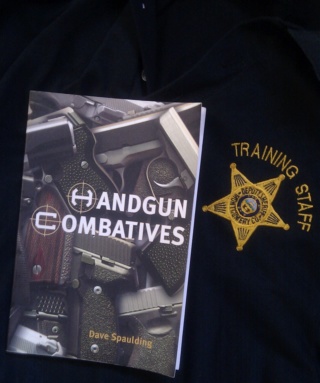

DENNIS: Our good friend Dave Spaulding has written a great book entitled HANDGUN COMBATIVES, in which he deals with Mindset and Situational Awareness in a very thorough way. You have contributed a chapter on Neural based training, and I was very impressed with your emphasis on experiential-based training for CQB. Could you give COMBAT readers an outline of why it is so important, and how we can incorporate this in our regular training?

MARCUS: Dave's book does an excellent job in the areas you mention; I think it will end up being a classic like PRINCIPLES OF PERSONAL DEFENCE or NO SECOND PLACE WINNER. Experiential based training? It's essential for combative skills or any skill set that has to be used under stress. Basically speaking, the state you learn a skill in is the state where you'll have the greatest recall of the skill. A state, for those who need to know, is the combination of your physiology (everything going on in your body, from hormone secretions to posture) plus your mental representation (which is everything going on in your mind). Common states include happiness, fear, anger, and so on. Each of those can be broken down into a specific physiology and specific mental representation. Quite often, we learn combative skills in a classroom or dojo or shooting range, and the state we're in when we're learning is one of being a student -- instead of being a practitioner using the skill. An example might be learning to swim. If you learned swimming only by doing the strokes on dry land, you'd have an understanding of what is necessary to swim in water; you might be able to demonstrate the various strokes. But until you're in the water using the strokes, you won't be proficient in the skill. Ineffective training teaches combat skills like swimming on dry land, but using those skills is like being dumped in the ocean during a storm. We train people on dry land and expect them to perform in open water during a storm. What we want to do during training is experience as much as possible the mental state necessary to survive close quarters battle (“ferocious resolve”), and to use their skills while in that state. Practising your basic skills while adding the mental representation of ferocious resolve accelerates your learning of those skills. Incorporating that element in your training will cement the retention of those skills in the part of the brain that will be called on to perform under stress when you have to use those skills. You can do this by adding visualisation to your drills, and emotional content. IN other words, if you're punching in the air to practice punches, visualise an opponent and add the emotional content of ferocious resolve to win and strike down your opponent. This is actually a part of all martial arts in the practice of kata or forms; if you're practising your forms as though you were actually fighting an opponent, those techniques will be available to you when you actually are fighting.

DENNIS: I'd like briefly to discuss self-protection hard skills. You mentioned a study which showed that operators from WW-2 were still able to perform CQB on demand. Recently there has been renewed interest in the teachings of Fairbairn, Sykes, Applegate and Styers. Would you recommend this approach? MARCUS: On the hard protection skills and the WW2 teachings -- Fairbairn, Sykes, Applegate and Styers were doing neural based learning without calling it that. I want to stress that much of what we've talked about is something that martial artists and warriors of all stripes have known for centuries. It's just in recent years that we've had the scientific basis and the vocabulary to describe the state, state management and sensory acuity elements. I think there's a lot of valid material in the WW2 training METHODS, the way they used reality simulation and training while under stress. That's the important thing, not the specific techniques of hand to hand or shooting or knife work. What made those techniques work was the mental platform of the operator, which was forged in reality simulation and training while under stress. I think the most powerful use of the WW2 stuff is to study HOW they did the training, and then adapt that approach to modern TECHNIQUE, meanwhile using the new language and experiential training drawn from NLP stuff. You put that all together, like you've done in your shooting programs, and you have the results that are literally incredible. The readers should know that in your shooting program you did in South Africa, you were able to take shooters who drew from concealment on an average of 2.0 seconds down to 1.2 and in some instances sub 1 second -- in the space of an hour. That kind of increase is possible if you concentrate on the mental platform, which is what the work of Fairbairn, Sykes, Applegate and Styers is all about. Much has been made of their techniques, but in my opinion their really earth shattering advances was in the HOW of doing training.

DENNIS: Your background in knife combatives is extensive, but the last time we trained together in edged-weapon work you were emphasising a very simple approach. You ditched most of the flow drills and carenzas in favour of a very direct, efficient system. My mate Simon James, has done the same, reducing much of the Filipino methods he has mastered into a very solid core. Care to comment?

DENNIS: Your background in knife combatives is extensive, but the last time we trained together in edged-weapon work you were emphasising a very simple approach. You ditched most of the flow drills and carenzas in favour of a very direct, efficient system. My mate Simon James, has done the same, reducing much of the Filipino methods he has mastered into a very solid core. Care to comment?MARCUS: One of the reasons I went to a very simple knife system has to do with the simplification of my own personal combative system. I'm older, my body is beat up with old injuries, I'm not in the best physical condition and I don't train the long hours I did twenty or thirty years ago. I've applied the KISS principle across the board with my personal combatives. But the reason I ditch3d a lot of the flow drills etc. is that they are just that: drills. Too often students mistake doing the drill for doing the technique in the real world. Most drills are designed to instil attributes as well as technique, and the Filipino systems stress flow, and many of the drills are designed to give you

flow. Well, if you already have flow, and you have that anchored properly to the fighting state, then you don't have to practice flow so much. If at all. I found the same thing in shooting. I used to shoot over 1500 rounds a month in training as a Federal Air Marshal. I now probably shoot less than 50 rounds a year. Despite that, I'm still able to shoot at an acceptable (to me) level of accuracy and speed, because I've trained that skill set in using neural based techniques.

[Marcus showing a knife drill in Sweden]

[Marcus showing a knife drill in Sweden]With blade work, a lot of what we spend time in the classroom doing is developing flow and continuity. If you've developed that, then you can concentrate on the important aspects: getting the blade into play, making the first cut, defanging your opponent and going for the kill.

One of the advantages of neural based training is that you cut (pun intended) to the essentials of the technique. With the blade, what do you want to do? Get it out, cut the opponent before he cuts you, and finish the fight. that's of course if that's what you want to do. It's important to realise that practising blade work as a martial art,... well, martial art is concerned with process -- the doing of the training is what is important. CQB and combatives are focused on outcome -- what you do with the martial technique.

What's essential with any weapon system is to understand that the primary platform, whether empty hand, blade or stick, or handgun and rifle, is the mind and the willingness of the operator, and that's anchored to state access techniques.

DENNIS: We reviewed your first novel "NO OTHER OPTION" here a while back, and it's become a best seller. Although fiction there is a lot of fact in the book, and I recognised several characters. There is also quite a bit of NLP isn't there?

DENNIS: We reviewed your first novel "NO OTHER OPTION" here a while back, and it's become a best seller. Although fiction there is a lot of fact in the book, and I recognised several characters. There is also quite a bit of NLP isn't there? MARCUS: There's a lot of NLP in there, especially in the action sequences that show Jonny Maxwell thinking through and doing state management, breathing control and the like. A couple of NLP practitioners of the therapeutic type have read the book -- but they won't talk to me anymore. Think it scared them off!

DENNIS: I don't think the mental processes of a hard operator have been better described than in NO OTHER OPTION. How is your next book coming along? MARCUS: My next book is titled WARRIOR IN THE SHADOWS and it comes out in hardback this September. The paperback of NO OTHER OPTION comes out in August. I've just finished the first draft of my third book, which I am in negotiations for publication right now.

DENNIS: Marcus, many thanks for an invaluable series of interviews. I know ourreaders will gain much to enhance their existing hard-skills training. COPYRIGHT 2001: © D. MARTIN

--------------

Details of Marcus' books

hereFor training with Marcus contact

here